For rehearsals, an outdoor room was used. Just outside the stage doors that adjoined the ball park the management had set up a canvas wall to separate the stage area from the park, with a wooden ceiling and canvas sides. This provided an ideal spot for the actors to rehearse in rain or sunshine (Gardener 4 June 1927).

Torrential rains greeted the opening of the 1927 season, yet a full house was in attendance. Quality Street, by J.M. Barrie, which opened on Sunday, 11 June, involves the Throssell sisters, Susan (May Buckley), a spinster who has had dreams of love, and Phoebe (Flora Sheffield), the younger, who plainly loves Valentine Brown (March), a dashing young physician who loves her but is not aware of his own affection. In the opening scene, Phoebe tells Susan and their spinster neighbors, the Misses Willoughby (Kirby Davis and Louise Huntington) and Turnbull (Adelaide George) that Valentine is coming to their home with an important message. All believe he will propose to Phoebe. When he announces instead that he has enlisted for the Napoleonic wars, all are astounded. After Valentine returns from the wars, nine years later, Phoebe attempts to rekindle the spark of romance they may have once had. March, as the dashing Captain Brown, was “thoroughly at home in the role” (Denver Post rev. of Quality St.). His first appearance in the play brought an outburst of applause, indicating that his fine work in the previous season had been well remembered. A local critic reported: “Fredric March returns as leading man, visibly improved after a winter’s work in the East. There is a flash in his eye, a little quickness of movement and a romantic dash to his bearing, that lent charm to his part of the young officer. A crisp incisive pronunciation aids the portrayal” (Monahan, Eve. News rev. of Quality St.).

George S. Kaufman’s The Butter and Egg Man opened the second week’s bill (19 June). The title was based on a phrase coined by Texas Guinan, a famous night club hostess, when one of her patrons had made himself conspicuous by insisting on buying everyone in the club a drink. When asked who he was, he mumbled that he was a dairyman from the mid-west. Texas Guinan then referred to the wealthy newcomer as a “butter and egg man,” and the slang expression became the identification of anyone from a small town who comes to a big city, trying to buy his way into society.

The play, therefore, tells the story of a small-town youth, Peter Jones (March), who inherits a small fortune and decides to become a theatrical producer. Conned by two would-be producers, Jack McClure and Joseph Lehman (Douglas Dumbrille and Ray Walburn), he buys a play, engages a company, and tries it out in Syracuse, only to have it fail. His partners leave him, but through the aid of his agent’s secretary, Jane Weston (Flora Sheffield), he manages to turn the tables and prove to be a big success.

Said one critic: as Peter Jones, March’s “transformation, in the final act, from a small-town hotel clerk to a successful play producer is one of the funniest sequences of the play” (DeBernardi, Eve. Post , 20 May). Another critic praised March’s “simplicity and comical pathos” (H.M.F., Morning Post , rev. of The Butter and Egg Man). The critic for the Morning News assessed more fully March’s talents:

The play provides (March) a corking opportunity and he never permits a moment of it to get by him. March becomes the uncertain youth in figure, voice and manner and not for a moment does he get out of character. When it comes to the painting of convincing characters, there is no one who knows how to do it better than Fredric March, and his performance last evening received a noisy evidence of appreciation from the audience. So skillfully does he handle some of his best comedy moments, that the audience cannot resist the temptation to shriek (Monahan, Morning News, 20 June).

Another witness observed that March “employs a queer high-pitched wavering tone, and sustains it admirably throughout the reading of long and many lines. The lines lifted from the text are not funny, but his manner of rendering them brings the laugh” (Eve. News, rev. of The Butter and Egg Man).

The following production on 26 June, Pigs, by Anne Morrison and Patterson McNutt, is set in a rural community in Indiana. Thomas Atkins, Jr.(March) would like to be a veterinarian, but his family opposes his wishes, except for his mother (May Buckley), who raises $250.00 for him with her engagement ring so that he may buy a litter of ailing pigs. Junior and his sweetheart, Mildred (Sheffield), nurse the pigs back to health and sell them when the price of pork soars. The older Atkins (Moffat Johnston) is obsessed with financial worries, but when Junior comes forward with money to aid his father, the latter for the first time realizes his son’s true worth.

No reviewer, said one critic, “could ever find fault with March’s performance in any role. Mr. March’s characterization of Thomas Atkins, Jr. is excellent”. Another witness observed that March “accelerates his walk into that of an impatient youth and again submerges himself in the role he assumes for the evening. A very thorough and fine performance” (Denver Post, rev. of Pigs).

The fourth week of the season, Arnold Ridley’s mystery-comedy, The Ghost Train, opened Sunday night, 3 July. The ghost train, a phantom string of train cars, passes by the station of an English branch railroad line periodically, at midnight. Anyone seeing the train drops dead mysteriously. The characters of the play, a casual 82 collection of travelers, are marooned in the haunted station on the night the death train is to pass.

March played the role of Teddie Deakin, a “lawfing, silly British ‘awss'” (Denver Post rev. of Ghost Tr.). Supposedly a brainless Englishman, Deakin in reality is a Scotland Yard detective. The Morning News stated:

March suits his voice and manner to the role and plays in a staccato fashion. One of the interesting features of playgoing at Elitch’s is the way this leading man puts himself into a role, rather than the role, into his own personality. Singing his praises is rather trite and one wishes he would do something not so well” (Morning News, 4 July).

The next bill, Willard Mack’s The Dove (July 10), was thought by many to be the best of the season. The story reveals the determination of the rich Mexican, Don Jose Tostado (Dumbrille) to win the service, if not the love, of Delores Romero (Penman), who, in turn, is enamored of Johnnie Powell (March), the American dice thrower who works across the street from the Purple Pigeon cafe, at which Delores is an entertainer. In a frame-up, Johnnie kills a shiftless cousin of Tostado’s and promptly goes to prison. Delores promises to give her affections to Tostado, if he will release Johnnie, which he does. But Johnnie tracks them down and saves Delores from ruin.

With a cast of more than 50 and four spacious and beautiful sets, Melville Burke offered a spectacular production. The Spanish and Mexican costumes, made in New York, were shipped to Denver on 5 July, just two days 83 before opening night. Said Lea Penman of the production, “In all my experiences in playing in costume productions, I never have seen anything put on with such care. The settings would be worthy of a Broadway production” (Penman, Evening Post, 12 June).

With Dumbrille and Penman as the leads, March took a secondary role as the card playing Johnnie Powell. The Morning News thought that March’s part “demands fire and he lights it with a real blast” (H.M.F. Morning News 8 July).

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, by Anita Loos and her husband John Emerson, was the sixth production of the season. It depicts two American gold-diggers seeking adventure in Europe. Lorelei (Sheffield), a wise little blonde from Little Rock, is sent to Paris by Gus Eisman, the button king of Chicago, to learn etiquette. Her unrefined and wisecracking girlfriend, Dorothy (Penman), accompanys her. On the boat over, Lorelei meets Henry Spoffard (March), a highly polished millionaire from Philadelphia, who falls in love with her. The girls progress through a series of comic episodes, which climax when Gus Eisman arrives in Paris to find her in the arms of another man. March as “the psalm-singing-risque-postcard-loving Henry Spoffard, cold and reserved of manner” gave ” the character an excellent portrayal” (Evening Post rev. of Gentleman P. Blondes).

Rolph Murphy’s Sure Fire, on 24 July, presented a young playwright, Robert Ford (March), who lives in Greenwich Village and has failed to make a living from his plays. He is advised by a successful producer and by an equally successful writer of Broadway hits to take a rest in a small town environment, where he will surely find the material for his drama. He goes to Clayville, Indiana, where he runs inadvertently into a plot concerning a grey-haired post-mistress (Buckley) with a pretty daughter (Sheffield), whose home is about to be foreclosed upon by the village skinflint (Dumbrille), because she has used mortgage money to pay her son’s gambling debts. Ford becomes his own hero, pays off the mortgage, and writes the successful play he had been striving for.

March was “thoroughly true to type and satisfying in the role” (Evening Post rev. of Sure Fire). The play had earlier failed in New York (running for only 32 performances); it likewise met with an indifferent reception at Elitch’s Gardens.

Sam Janney’s Loose Ankles, the season’s eighth production, involves Gil Barry (March), a young man who wants to be an archeologist but by financial necessity is driven into becoming an escort/dancer. He and his three companions (Johnston, Dumbrille and Mackenzie Ward) earn their living by dancing with overweight ladies, and then receive valuable presents from them. Ann Harper 85 (Sheffield), a rebellious young flapper, will inherit a fortune if she marries someone acceptable to her family. To momentarily appease her family’s worries, she hires Barry to impersonate her boyfriend and unintentionally falls in love with him. The Post commented that “[March] shows close attention to the mechanics of his part and does a good piece of work” (“Loose Ank. , Smart Comedy”). Monahan classified March’s portrayal of a “lugubrious, hesitant dreamer,” as a part “made for him” ( Eve. News 1 Aug.).

On 7 August, the ninth production, The Last Mrs. Cheyney, premiered. Billed as the most brillant comedy to be written in the last ten years, it offered the best role of the season for Flora Sheffield. Written by Frederick Lonsdale, the play’s plot has the mysterious Mrs. Cheyney, impersonating an Australian aristocrat, wooed by the pompous and wealthy, Lord Elton (March). In reality a member of a gang of crooks, her identity is discovered by Dilling, who confronts her when he catches her stealing a string of pearls. Faced with disclosure, Mrs. Cheyney produces a letter in which Lord Elton discloses scandalous tidbits about his fellow peers and to keep her silence, Mrs. Cheyney is acquited of charges.

March, as Lord Dilling, a wealthy young bachelor with a reputation among women, succeeded “admirably” in depicting the qualities of “gentleman and philanderer” (Morning News rev. of The Last Mrs. Cheyney). The play was praised for its “brilliant exhibition of word fencing” and “constant clash of wits” (Morning News).

In the following week, the company presented Lula Vollmer’s The Shame Woman, a story of the Carolina mountains and the efforts of a single mother to protect her adopted daughter from the stigma of having fallen in love with the wrong man. The season’s tenth production (opening 14 August), it marked the Denver debut for actress Florence Rittenhouse in the role of Lize Burns, which she had created in the original New York production and had played for over 270 performances.

Having lived for twenty years in a lonely North Carolina cabin, Lize Burns is branded as a fallen woman by her neighbors because of her affair years before with the mayor’s son, Craig Anson (March), who abandoned her and bragged to people of Lize’s promiscuity. She lives with her daughter Lily (Sheffield), an adopted orphan whom Lize had nursed back to health from a fever epidemic. She adores the young girl and feels undeserving of Lily’s unconditional love. When Lize discovers that her daughter has been seeing a married man, she reveals to Lily her own sad tale of abandonment. Inconsolable, Lily kills herself. When the lover calls at the cabin for Lily, Lize recognizes him as Craig Anson. To prevent him from once again “laughin’ and tellin’,” Lize stabs him to death. 87 Refusing to permit her daughter’s good name to be “shamed,” Lize goes to the gallows for the murder of Anson.

Although his role was brief, March gave “a fine performance; extremely credible and believable” (H.M.F. Morning News).

Two weeks prior to the opening of Spread Eagle, by George S. Brooks and Walter B. Lester, Denver advertisements had promoted the fact that in this eleventh production of the season, Fredric March was to have the best role “ever assigned to him” (Denver Post 22 Aug.). The plot concerns Martin Henderson (Moffat Johnston), the guiding spirit of a gigantic corporation whose battlements extend to every far-flung corner of the world. In order to protect his threatened Mexican mining interests, Henderson finances a revolution, and, to make certain that the United States government will intervene and save his property, employs the son of a former U.S. president to take a precarious position at one of his mines, fully cognizant that the boy, Charles Parkman (Allen Vincent), is apt to be murdered by Henderson’s own revolutionists.

March played the role of Joe Cobb, special assistant to Martin Henderson, who, after discovering Henderson’s scheme, deserts Henderson to work out his own salvation. While Martin Henderson motivates the plot, Joe Cobb is at the center of the play’s action. Cobb deplores doing 88 Henderson’s “dirty work,” quits, joins the army, and in the final scene, returns to tell his boss what he really thinks of him.

March stated in an interview that he looked forward to playing the role of Joe Cobb: “Cobb is the composite of thousands of disillusioned men all over the U.S. today. His cynicism, his ability to turn a grim moment into a laugh, his very humanness make him a person rather than a character” (March Denver Post, 21 Aug.). Debernardi of the Denver Post reported that “[March] has the outstanding role of his career. [Cobb] is a forceful, typical, cynical man who has no illusions about the glamour of war” (22 Aug.). The Morning News called March’s portrayal “superb”. Details of the performance can be seen through the pen of the Evening News critic:

March plays Joe Cobb. He plays it as he has never played a role before. With all the vigor and excusable vitriol the part demands. That last time he speaks, just as the curtain falls is beautiful. He hurls it at Henderson, the murderer and dollar-a-year man. In it he seems to epitomize all the hatred for hypoccrisy [sic] concerning war, expressed by cynical men at arms since the world began (What Price Glory Finds Sequel in Spread Eagle”).

The final production of the 1927 season, The Cradle Snatchers, a farce written by Russell Medcraft and Norma Mitchell, had played 332 performaces on Broadway with Humphrey Bogart playing the role of Jose Vallejo. The play focuses on three matrons who, discovering that their husbands are philandering under the guise of a hunting 89 trip, hire three college gigolos to entertain them, in the hope that their flapper-chasing husbands will become jealous and return to the home fires. May Buckley, Kirby Davis, and Florence Rittenhouse played the three matrons, and Allen Vincent, March, and Frank McDonald (the company stage manager) portrayed the three collegiates.

When the three young adventurers arrive at Mrs. Ladd’s Long Island summer home, and March, as Jose Vallejo, announces that he is going to “give his mamma full weight for her money,” the Elitch theatre audience erupted with wild applause. In the end, the husbands do return home, find their wives in compromising situations, and give in to the complaints of their mates.

Reported the Denver Post: “March played the pseudo-Spanish osteopath, Jose Vallejo, with all the fire and comedy flair the part calls for, taking round after round of applause for his work” (“Cradle Snatchers Gets Laughs”). March’s role was filled with “poetic speeches,” which he presented to the audience in “splendid fashion,” with a roar following each (Morning Post, 29 Aug.). The Cradle Snatchers was a “cleverly written bit of stage stuff,” according to the Post (29 Aug.), filled with sparkling lines of comedy, fast action, and laugh provoking situations.”

Summary of the 1927 Season

With the close of The Cradle Snatchers, the Elitch’s Gardens theatre closed the most successful artistic and 90 financial season in its history (Mulvihill The Gardener 2 Sept.). While the maintenance of a company of the standard of the Elitch Players was not primarily one for financial profit but rather an aim to provide the citizens of Denver with an opportunity to witness good plays presented by actors of the best talent obtainable, the financial success of the season was a gratifying one (Mulvihill 1). Every effort had been made to give a wide variety of plays, including the most recent New York successes. Emphasis was placed on comedy, in the belief, sustained by box-office figures, that the public enjoys amusing summer entertainment, if it is intelligent and well presented.

More than 200 plays were read by Mulvihill and Burke in an endeavor to secure twelve that would be of a certain standard of entertainment. Mulvihill and Burke made three trips to New York between October and May, viewing each attraction on Broadway. Out of the plays offered in 1926 on Broadway, Mulvihill and Burke decided that The Ghost Train for mystery, Sure Fire, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, and Loose Ankles for comedy and Spread Eagle for drama were the best of the lot. The Last of Mrs, Cheyney, Pigs, and The Dove were secured after an order had been placed with the agency a year in advance to buy them immediately when they were on the market. (The Elitch Gardener, 8-28-27 7).

The 1927 season had offered March the opportunity to play varied character parts. In twelve weeks March successfully performed the roles of an army physician, a novice theatre producer, a pig farmer, a Scotland yard detective, a professional gambler, a millionaire, a struggling playwright, an escort/dancer, a Lord, a scoundrel, a secretary with a conscience, and a college gigolo. Each of his performances was critically acclaimed by the Denver critics, and his popularity with Denver audiences was acknowledged by all connected with the Elitch theatre.

With the end of the Elitch season, March and Eldridge returned to New York to begin rehearsals for the Theatre Guild’s first national tour, for which Eldridge was hired to play the leading lady roles in four plays which the Theatre Guild had produced in New York with success: Arms and the Man, The Guardsman, The Silver Cord, and Mr. Pim Passes By. March was hired to play featured roles.

The Theatre Guild Tour of 1927-28

During the 1920s, and to a lesser extent, during the 1930s, the most dynamic and creative organization on Broadway was the Theatre Guild (Atkinson 209). Not interested in commercial gain but in establishing an art theatre with modern standards, the Guild’s humble 92 beginnings in 1919 with a group of amateur producers, was never expected to succeed. However, by 1929, the Guild had four productions simultaneously playing in four theatres on Broadway and seven companies traveling across America (Atkinson 213). The Guild was committed to producing plays of artistic merit and most of its early plays came from abroad. Unintimidated by public opinion, the Guild took an interest in Bernard Shaw, who in 1920 was in disgrace for his opposition to World War I. At the beginning of its third season, the Guild gave the world premiere of Heartbreak House, an audacious play by Shaw, which met with great success.

Believing that audiences throughout America were as hungry for good theatre as were New York consumers, the Guild in 1926 began plans to take four of its most successful artistic works on tour. Under the leadership of two of its directors, Lawrence Langner (founder of the Guild and later founder of the American Shakespeare Theatre and Academy at Stratford, Connecticut) and Theresa Helburn (a past student of G.P. Baker’s at Harvard), the Theatre Guild began its first national tour in October of 1927 (“The Guild Plans a Tour” Theatre Guild file).

Remembering that Florence Eldridge had been quite successful in the Guild’s 1921 Ambush production, Langner and Helburn wished to team her with well-known actor George Gaul; they would play the leads in the experimental 93 touring company. Aware of Fredric March’s developing popularity in New York and his success at Elitch’s, Langner and Helburn thought that March would be an added strength in featured roles. (“The Guild Plans a Tour” Theatre Guild File ). Contacted in Denver, during the 1927 summer season, March and Eldridge were ecstatic to have such an opportunity made available to them and they signed a contract with the Guild in June 1927. (“Ridgewood Claims Eldridge”, Ridgewood Times).

[Parrish, Vicki Payne. “The American Stage Careers of Fredric March and Florence Eldridge,”]

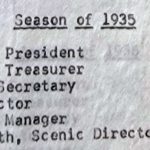

Theatre Staff:

- J. M. Mulvihill, President

- George L. Roberts, Treasurer

- Melville Burke, Director

- Frank McDonald, Stage Manager

- G. Bradford Ashworth, Art Director

Resident Compan

- Florence Rittenhouse

- Flora Sheffield

- May Buckley

- Louise Huntington

- Lea Penman

- Uytendale Allaire

- Frederick March

- Douglas Dumbrille

- Moffat Johnston

- Mackenzie Ward

- Raymond Walburn

- Clyde Fillmore

- J. Hammond Dailey

- Allen Vincent.

Productions:

- Week of June 11: Quality Street, by J.M. Barrie

- Week of June 19: The Butter and Egg Man, by George S. Kaufman

- Week of June 26: Pigs, by Anne Morrison and Patterson McNutt

- Week of July 3: The Ghost Train, by Arnold Ridley

- Week of July 10: The Dove, by Willard Mack

- Week of July 17: Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, by Anita Loos and John Emerson

- Week of July 24: Loose Ankles, by Sam Janney

- Week of Aug. 7: The Last of Mrs. Cheyney, by Frederick Lonsdale

- Week of Aug. 14: The Shame Woman, by Lula Vollmer. Florence Rittenhouse, playing her original role of Liza, became leading lady of the company.

- Week of Aug. 21: Spread Eagle, by George S. Brooks and Walter B. Lister. Allen Vincent joined the company, playing his original role of Charles.

- Week of Aug. 28: The Cradle Snatchers, by Russell Medcraft and Norma Mitchell.